July 21, 2010

A needed change of perspective

We recently read two articles that suggest that we need to shift our perspective a bit to realize just how vital classical music is to our world today.

July 15, 2010

Gonzalo in the Wall Street Journal

One of the volunteers who is helping us with our season ticket mailing mentioned this morning that Gonzalo Ruiz is featured in today's Wall Street Journal. He talks about transcribing Bach's "Orchestral Suite No. 2," with it's famous flute solos, for oboe. We played this back in October 2008 to rave reviews.

One of the volunteers who is helping us with our season ticket mailing mentioned this morning that Gonzalo Ruiz is featured in today's Wall Street Journal. He talks about transcribing Bach's "Orchestral Suite No. 2," with it's famous flute solos, for oboe. We played this back in October 2008 to rave reviews.Hear for yourself:

July 12, 2010

Fun — and fart jokes — in classical music

That was the sub-headline of the great feature in The Aspen Times this weekend on our Music Director.

That's right, so soon back from Oregon and Nic's off in Aspen (and we wish we could go see him conduct, but we'll have to wait until September when our 30th Season kicks off).

Here's a bit of our favorite part from the article:

"McGegan believes that injecting that sort of jollity into classical music is hardly a radical notion, or even a departure from early concert-going.

"'Mozart loved it when people clapped in the middle of a movement,' he said. 'I have no problem with people clapping between movements. If you're playing Mahler Nine, it's a different atmosphere than [Mozart's] 'Jupiter' Symphony, or Haydn, which had genuine jokes in it.' McGegan mentions a Haydn passage in which two bassoons play some loud, rude notes: 'It could only be associated with the back end of a cow. You can be sure the original audience laughed their asses off.'

"The notion that classical music is strictly serious business wasn't around at the birth of concert music. McGegan imagines a dinner party where the guests are all noted composers, and he believes there would be plenty of drinking, laughter and off-color behavior.

"'Haydn would be delightful, charming. Mendelssohn — wonderful,' he said. 'Mozart would probably tell naughty jokes and fart and throw bread rolls at the women. He wasn't well-trained for the house. Poor Beethoven — he'd probably be tortured, because he couldn't hear the conversation. Wagner would just talk about himself.'

"A review of a recent concert McGegan did with the Philadelphia Orchestra referred to McGegan and Robert Levin as 'the two naughty boys of early music.' But McGegan finds nothing inappropriate about his approach to music. When the music calls for an austere respect, he has no trouble moving into a more solemn mode. In any event, his credentials as a proper gentleman were solidified last month, when he was named an Officer of the Order of the British Empire.

"But McGegan sees his role not so much as standing erect next to the queen, but in getting the classical music world off its high and mighty throne."

June 25, 2010

Soccer: Baroque? Classical? Romantic?

June 22, 2010

More Nic News

Last week, Juilliard's Historical Performance program announced that Nic will conduct Juilliard415 on Saturday, November 20 at 8 PM in Alice Tully Hall. The program includes a rare Handel cantata, Clori, Tirsi, e Fileno, and Vivaldi's Concerto for Two Flutes in C Major. Having only just debuted in December of last year, Juilliard415, the music school's new period-instrument group, will perform a series of seven concerts next season that features not only Nic, but also Jordi Savall and William Christie. Watch them perform with Artistic Director Monica Huggett below.

Last week, Juilliard's Historical Performance program announced that Nic will conduct Juilliard415 on Saturday, November 20 at 8 PM in Alice Tully Hall. The program includes a rare Handel cantata, Clori, Tirsi, e Fileno, and Vivaldi's Concerto for Two Flutes in C Major. Having only just debuted in December of last year, Juilliard415, the music school's new period-instrument group, will perform a series of seven concerts next season that features not only Nic, but also Jordi Savall and William Christie. Watch them perform with Artistic Director Monica Huggett below.June 8, 2010

Our new favorite blogger...

June 7, 2010

An inspiring model?

May 25, 2010

Closing out 20 years: Nic and the Göttingen International Handel Festival

Today, our Music Director Nic (left) conducted the final performance of the Göttingen International Handel Festival – the dark opera Tamerlano (HWV 18). Nic has led the Festival as its Music Director for the last 20 years. In 1991, he was passed the baton (figuratively of course, Nic doesn't use a baton as you may remember) by Sir John Eliot Gardiner. Next year, Nic will pass the honors of leading the Festival to (fittingly) yet another British conductor – Laurence Cummings. This year was the Festival's 90th year – to learn more about the festival, watch this video.

Today, our Music Director Nic (left) conducted the final performance of the Göttingen International Handel Festival – the dark opera Tamerlano (HWV 18). Nic has led the Festival as its Music Director for the last 20 years. In 1991, he was passed the baton (figuratively of course, Nic doesn't use a baton as you may remember) by Sir John Eliot Gardiner. Next year, Nic will pass the honors of leading the Festival to (fittingly) yet another British conductor – Laurence Cummings. This year was the Festival's 90th year – to learn more about the festival, watch this video.March 19, 2010

Into the crazy world of Orlando: From our Handel expert (and Music Director) Nic McGegan

Nicholas McGegan joins us again to let us know what's so special about George Frideric Handel's opera Orlando, which the orchestra and chorale will perform in April:

Pictured above is the autographed score of Orlando, one of a series of so-called magic operas by Handel. While the sources of many of his plots are derived from classical history or mythology, the 1733 opera Orlando (as well as Ariodante and Alcina, both of 1735) is based on an Italian epic poem from the Renaissance – Orlando furioso by Ludovico Ariosto. Its story is one of extravagant valour and passion taken to the point of madness. Indeed, one could say that works in this genre were parodied by Cervantes in Don Quixote.

Extravagance, passion and madness are, of course, the life blood of opera and it is clear that Handel was inspired by the subject to produce one of his finest works. This is the last opera he wrote for the great alto castrato Senesino (left) for whom he had composed operas for a dozen years. Senesino was a difficult character but a superb singer and, unlike Farinelli, a splendid actor. This must have been a perfect role for him. The Mad Scene that forms the climax to the Second Act is one of the moments of Baroque Opera. Gone are all the normal conventions of the genre, even normal rhythms go awry as Orlando descends (in his own deluded mind) into Hell in five/eight time.

Into this crazy world, Handel, or rather his librettist, introduces two characters who are not found in Ariosto’s original. One is the magus Zoroastro who watches over the mad Orlando and eventually cures him of his insane love for Angelica. He is a wise father figure who will reappear in the Magic Flute as Sarastro. The other is the shepherdess Dorinda who represents an ordinary ‘down to earth girl’ mixed up in the rarified world of chivalrous romance. Her reactions are sometimes comic but she is also emotionally hurt by the crazy grandees about her, who use her and occasionally abuse her. However, she is the contact between us, the audience, and the other characters. This role was created for Celeste Gismondi, a Neapolitan comedienne, newly arrived in London. Obviously, she was an excellent singer and pert actress. It is with her character that we most often sympathise.

Handel’s music is of the highest level throughout and, because of the story, he was inspired to experiment with glorious results. Apart from the famous Mad Scene, the Trio at the end of the First Act is one of the finest ensembles he ever wrote and the aria during which Orlando finally collapses would not be out of place in a Bach Passion.

.jpg) All this emotional extravagance was matched on stage by new scenery and costumes (like pictured left) specially made for the production. This was unusual at the time and was even noted in the newspapers. In addition, there were flying machines, including a chariot drawn by dragons to take Orlando out of Hell. We are, of course, giving the work in concert, so the audience will have to imagine the magic world on stage that went hand in hand with Handel’s glorious music.

All this emotional extravagance was matched on stage by new scenery and costumes (like pictured left) specially made for the production. This was unusual at the time and was even noted in the newspapers. In addition, there were flying machines, including a chariot drawn by dragons to take Orlando out of Hell. We are, of course, giving the work in concert, so the audience will have to imagine the magic world on stage that went hand in hand with Handel’s glorious music. March 11, 2010

Size matters: About the length of natural horns

My wife and I greatly enjoyed the early French-Handel-Telemann concert last night. We were intrigued by the two-foot-long trumpets and the extra curly horns. I opined that maybe the extra pipe functioned much as today's brass mutes do, softening the sound and helping it to combine with other instruments. (But I'm willing to be proven wrong.) Your explication, please?

Ensembles like Philharmonia Baroque, which play early music on period instruments (i.e. instruments like the ones used in the period in question, the 17th and 18th centuries in our case), use trumpets and horns without valves. For these "natural" instruments, the length of the instrument (that is, the length of brass tubing) determines the fundamental pitch of the instrument and, by adjusting the tension of the lips, the player can produce the notes in the harmonic overtone series of that fundamental pitch.

Ensembles like Philharmonia Baroque, which play early music on period instruments (i.e. instruments like the ones used in the period in question, the 17th and 18th centuries in our case), use trumpets and horns without valves. For these "natural" instruments, the length of the instrument (that is, the length of brass tubing) determines the fundamental pitch of the instrument and, by adjusting the tension of the lips, the player can produce the notes in the harmonic overtone series of that fundamental pitch.In the 19th century, instrument makers started experimenting with keys and valves which would allow the player to have an instrument that was the maximum length he would ever need, but would allow him to artificially shorten the length of tubing by diverting the airflow by means of opening or closing valves. Bernard D. Sherman writes in the recent article in Early Music America Magazine:

Inventors first applied valves to the horn in 1814, yet the results still sounded “intolerable” in the 1820s to the foremost composer for the instrument, Carl Maria von Weber. In the 1830s, when Brahms was born, a Viennese inventor patented an essentially modern valve, and the Parisian composer Jacques Halévy published the first orchestral parts conceived purely for valved horns. They were to be played alongside the old and tellingly named natural horns. Such hybrid scoring continued in the 1840s, with examples from Robert Schumann and Richard Wagner.

March 2, 2010

Like the human voice...

Though Toronto indie rocker Charles Spearin's Happiness Project is one the most touching explorations of humanity through sound in recent memory, he is not exploring a new idea – musicians and composers have long tried to replicate the beauty of the human voice and patterns of speech instrumentally. In particular, bowed stringed instruments have always been admired for their ability to mimic the human voice.

Though Toronto indie rocker Charles Spearin's Happiness Project is one the most touching explorations of humanity through sound in recent memory, he is not exploring a new idea – musicians and composers have long tried to replicate the beauty of the human voice and patterns of speech instrumentally. In particular, bowed stringed instruments have always been admired for their ability to mimic the human voice.January 7, 2010

The Story of "A:" More about Baroque pitch

Baroque oboe legend Bruce Haynes has researched the issue of historical pitches in detail. I suggest reading his book The Story of “A” if this post interests you. Bruce points out that we talk about pitch levels by means of two coordinates, a pitch name and a frequency in hertz, e.g. “A-415.” For about the last century, the standard pitch level has been A-440, meaning that, wherever you go in the world, Western classical music is likely to be played at a pitch level in which the note A in the middle of the treble staff is tuned to 440 hz. (Editors note: a hertz is a unit of frequency – one cycle per second – that measures, in this case, the traveling wave or oscillation of pressure caused by vibrations that we discern as sound). Having a pitch standard is a convenience for musicians, nothing more.

Prior to the late 19th century, however, there were no universally recognized pitch standards. One could travel from one part of Europe or, in some cases, from one city to another and find music being made at different pitches. For a string player, this in no problem – the string can be tuned to any pitch (within reason) – but for a fixed-pitch instrument, like a flute or an oboe, this can be a huge problem. It might mean that if you were an oboist, you could play in tune with a violin band but not with the church organ, or you could form your own band with your friend with a recorder made in your village but not with your friend with a recorder from the next town over.

Prior to the late 19th century, however, there were no universally recognized pitch standards. One could travel from one part of Europe or, in some cases, from one city to another and find music being made at different pitches. For a string player, this in no problem – the string can be tuned to any pitch (within reason) – but for a fixed-pitch instrument, like a flute or an oboe, this can be a huge problem. It might mean that if you were an oboist, you could play in tune with a violin band but not with the church organ, or you could form your own band with your friend with a recorder made in your village but not with your friend with a recorder from the next town over.In the Baroque Era, pitch levels as high as A-465 (17th century Venice) and as low as A-392 (18th century France) are known to have existed. A few generalizations can be made:

- pitch was high in North Germany and lower in South Germany

- pitch was low in Rome but high in Venice

- pitch in France depended on whether you were playing chamber music, opera or something else.

One of the pitches used during the baroque period was A-415. Since 415 hz. is about a half-step below the modern standard of A-440, the pitch of A-415 was seized on as a convenient modern “baroque pitch” standard, because in the early days of the historical performance movement a harpsichord would sometimes play with groups at A-440 and sometimes at a lower pitch, and if the difference in pitch is a half-step, the keyboard could be made so that it slides over one string so that the A key played a string tuned to 440 hz. in one position and a string tuned to 415 hz. in the other position.

“So when you play baroque music, you tune to a G-sharp,” some people say at this point. Not so! We tune to an A, but we define the A differently depending on what kind of music we’re going to play. A baroque violinist may carry 4 different tuning forks (or one handy iPhone app), and a baroque flutist probably owns two or three different flutes at different pitches.

December 7, 2009

Learning French... Baroque String Techniques

December 4, 2009

Composer Warbucks: Vivaldi and the Ospedale della Pietà

The Pio Ospedale della Pietà in Venice (image below), usually described as an orphanage and music school, was extremely important in Antonio Vivaldi’s life. At the age of 25, Vivaldi was hired by the Pietà as a violin teacher. It was his first “real” job, and his association with the Pietà continued in one form or another for the rest of his life. A great deal of Vivaldi’s music was written for concerts and religious services at the Pietà.

In 1198, Pope Innocent III decreed that homes should be established which would care for orphans and children who had been abandoned. These homes were generally associated with churches and convents. By means of a “baby hatch” or “foundling wheel” (image below), a mother could anonymously deliver a baby, usually a newborn, into the care of the church. The mother would place the baby in a sort of revolving door, rotate the device so that the baby was inside, and then ring a bell to alert those inside that a baby had been delivered. Sometimes babies were abandoned because of a deformity, but more often it was because they had been born out of wedlock.

In fact, as Robert Mealy wrote in last season’s program notes for March 2009’s “Winds and Waves” concerts: the young women had to renounce any professional career once they left the institution.

“These terms meant that there were a good number of women who stayed on in the Pietà, becoming teachers. This all-woman orchestra was enough of a novelty (and their playing was of such exceptional ability) that their performances became one of the attractions of Venice, a standard stop on the Grand Tour of young, well-to-do gentlemen, who delighted in the mystery of hearing these women play behind a “grille” or screen.”

November 30, 2009

The Red Priest

When Antonio Vivaldi was born in 1678, his father Giovanni was a professional violinist employed by the Basilica of San Marco in Venice. Antonio no doubt studied violin with his father and, by time he was a teenager, he was occasionally subbing for his father at San Marco and being hired at the basilica as an extra player for special occasions.

Despite this background in music, Vivaldi’s life seemed to be aimed at the priesthood. He was known during his life as “The Red Priest,” a reference to his red hair. He studied for the priesthood at several churches in Venice beginning when he was 15 years old and was ordained at the age of 25. However, within a few years of his ordination, he permanently stopped celebrating Mass, but still retained his status as a priest (and presumably retained other priestly functions, such as hearing confessions).

Famous 1723 caricature of "Il prete rosso" by Pier Leone Ghezzi.

The reasons for this change are unclear. Vivaldi is known to have suffered all his life from bronchial asthma, which could possibly have interfered with his ability to speak and chant for the duration of a Mass. There is a story, almost certainly spurious, that Vivaldi once left the altar in the middle of Mass to return to the sacristy. In the story, the reason was that a clever fugue subject had just occurred to him and he wanted to write it down before he forgot it. If the story is true, it could also be that he had an asthma attack during Mass and needed to sit down. It is also known that some years later, Vivaldi was censured for conduct unbecoming a priest. Although the reason for Vivaldi’s censure is unclear, it is also possible that the reason was also related to his decision to stop celebrating Mass.

Despite the fact that Vivaldi did not celebrate Mass and despite any difficulties with the church hierarchy, he was known during his life as a pious man and frequently wrote an abbreviation of the religious motto “Laus Deo Beataeque Mariae Deiparae Amen” on his manuscripts.November 5, 2009

Tonight's the night!

Dario_Acosta.jpg) Tonight, our orchestra and chorale perform the first concert of our November program that features Dido and Aeneas and other works by the beloved English composer Henry Purcell. In celebration of the anniversary of the composer's birth (350 years ago this fall!), Music Director Nicholas McGegan conducts Susan Graham (left) and a stellar cast of singers at Herbst Hall in San Francisco. It would be an understatement to say that we are giddy with anticipation here in the office.

Tonight, our orchestra and chorale perform the first concert of our November program that features Dido and Aeneas and other works by the beloved English composer Henry Purcell. In celebration of the anniversary of the composer's birth (350 years ago this fall!), Music Director Nicholas McGegan conducts Susan Graham (left) and a stellar cast of singers at Herbst Hall in San Francisco. It would be an understatement to say that we are giddy with anticipation here in the office.A masque? Let's ask...

The music of masques was clearly important, but little is known about these pieces because almost no complete scores have survived. This is why so few masques are reconstructed for modern audiences (and probably why so many of us are asking: what’s a masque?). It is suspected that violin bands accompanied the main dances and sometimes woodwind bands the professional dancers. Probably while accompanying themselves on lutes, an ensemble of royal singers would introduce or comment on the dances through songs, many of which were popular beyond the walls of the court.

November 2, 2009

Learn more about our November concerts

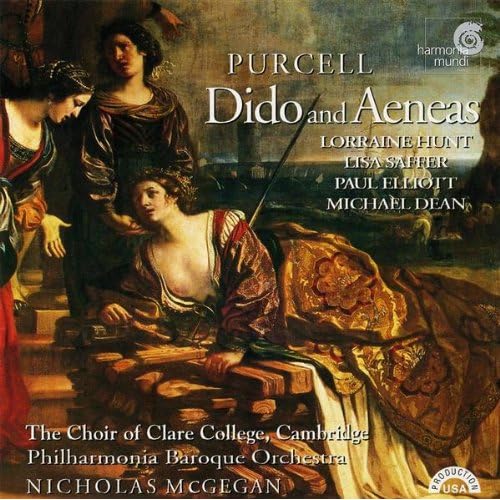

"The Passion of Dido," Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra's third concert of its 2009-10 "Season of the Stars," is THIS WEEK! Music Director Nic McGegan (pictured left) leads our orchestra and chorale in a program that honors the life of the English composer and songwriter Henry Purcell. Featured on the second half of the program is Dido and Aeneas with renowned mezzo-soprano Susan Graham singing the role of Dido and also William Berger, Cyndia Sieden, Celine Ricci, Jill Grove and Brian Thorsett. In it's last issue, Early Music America Magazine wrote about our recording of Dido and Aeneas:

"The Passion of Dido," Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra's third concert of its 2009-10 "Season of the Stars," is THIS WEEK! Music Director Nic McGegan (pictured left) leads our orchestra and chorale in a program that honors the life of the English composer and songwriter Henry Purcell. Featured on the second half of the program is Dido and Aeneas with renowned mezzo-soprano Susan Graham singing the role of Dido and also William Berger, Cyndia Sieden, Celine Ricci, Jill Grove and Brian Thorsett. In it's last issue, Early Music America Magazine wrote about our recording of Dido and Aeneas:

What is, to my mind, the finest Dido and Aeneas recording currently available features an American cast and orchestra. The 1993 Harmonia Mundi recording with the late mezzo-soprano Lorranie Hunt Lieberson in the title role has it all. For sheer gorgeous vocalism wed to dramatic intensity, Lieberson is unsurpassed. Her every phrase and gesture carries weight. Lieberson's singing of the lament? I had to sit in silence afterward and collect myself... This recording, with [Nicholas] McGegan leading a remarkably responsive Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, cuts to the heart of the work. The Dido and Aeneas (sung by baritone Michael Dean) exchange in Act III seethes, and Lieberson's cry of 'By all that's good!' is shattering. For once, the roles of the Sorceress (mezzo-soprano Ellen Rabiner) and the Witches (sopranos Christine Brandes and Ruth Rainero) are colorful but not so broad as to descend into Monty Python parody."

"McGegan and the orchestra are buoyed, not bowed down, by their specialist knowledge, and undaunted by the technical difficulties of some of the older instruments. They master intricate rhythmic and phrasing details that you don’t normally hear from modern instrument orchestras, yet play them with a conviction and ease that sounds natural. McGegan’s adrenaline-filled gestures transmit his excitement, and the orchestra normally responds by lifting you out of your seat. This is music-making by people who have been to the early-music revolution and come back enriched." Read more of Michael Zwiebach's preview.