February 23, 2010

How's your Catalan?

February 17, 2010

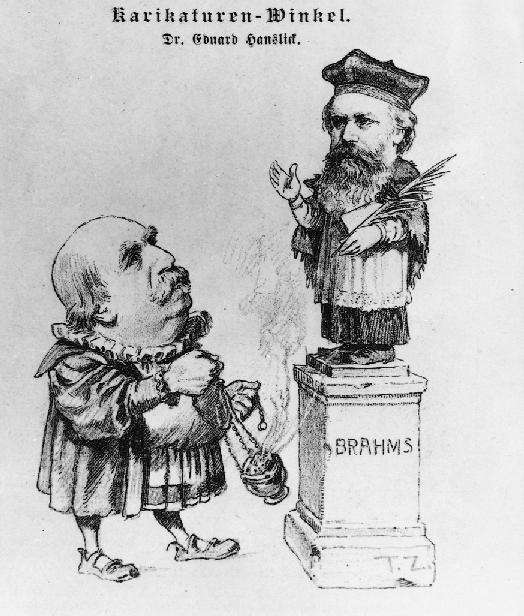

What did you think about our Brahms concert?

Music director Nicholas McGegan prefaced the concert with a few words about the attempts at the historical accuracy on display... All very interesting, but the real test came in performance. And nothing affirmed the power of this approach like the splendid performance of the Serenade No. 1 in D that occupied the first half of the program... Avoiding the sleek, sometimes impersonal quality that can often seep into modern renditions, [McGegan] embraced every opportunity to give the music a musky physicality - especially in the outer movements, whose rhythmic force was arresting.

Were Johannes Brahms alive to coach today's players, what instructions would he give them? How would he want his music to sound? Not the way it sounded Thursday, when conductor Nicholas McGegan and the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra unveiled their much-ballyhooed all-Brahms program... It was one strange concert, beginning with an almost stupendously inept performance of Brahms' infrequently played Serenade No. 1 in D major... At its base line, the concert was plain uncomfortable... The orchestra sounded like a country band, raucously out of tune, with broadly sliding strings and elephantine mishaps in the winds and horns.

February 10, 2010

Nic on performing Brahms: Pt. 5

Orchestra size and arrangement –

Orchestra size and arrangement – - Brown, Clive. 1999. Classical and Romantic Performance Practice 1750-1900. Oxford University Press.

- Haynes, Bruce. 2002. A History of Performing Pitch (The Story of “A”). Scarecrow Press.

- Lawson, Colin, and Robin Stowell. 1999. The Historical Performance of Music, an Introduction. Cambridge University Press.

- Musgrave, Michael, and Bernard D. Sherman. 2003. Performing Brahms. Cambridge University Press.

February 9, 2010

Announcing 2010-11 – Our 30th Anniversary Season

February 8, 2010

Tomorrow's the day...

Nic on performing Brahms: Pt. 4

Nic continues his post about the style that the orchestra will perform Brahms in this week:

Brahms was notoriously metronome-averse, so neither of the pieces that we will be playing are provided with metronome markings. Joachim, however, had no such qualms, and his edition of the Violin Concerto (1910) does have them. In the German edition of Joachim’s Violinschule (1905), which contains the violin part of the concerto, there are faster markings than in the 1910 edition; those are given here in parenthesis. They are:

Mvt. 1. Quarter note =120 (126).

Mvt. 2 Eighth note = 72

Mvt. 3 Quarter note = 96 (104). Poco più presto, Quarter note = 120 (132)

These however are not to be thought of as tempi that apply to a complete movement. There is plenty of evidence to show that Brahms, like many of his time, preferred a very flexible approach to speed. The orchestra will try this, at least in the Serenade. There is a wide variation in the overall timings of some Brahms’ Symphonies from one performance to another. For example, Symphony No. 1 was performed in 37 minutes by Hans von Bülow and the Meiningen Orchestra in 1884, compared to Carlo Maria Giulini and the L.A. Philharmonic in 1981 at slightly over 49 minutes.

Pitch –

We will be tuning to A-440. When touring, Richard Mühlfeld would send a tuning fork ahead to the next venue so that the piano could be tuned to the right pitch. His fork was at A-440. This was, however, by no means the universal pitch at the time. ‘Pitch battles’ were fought all over Europe between instrumentalists, who favoured a higher pitch, and opera companies, whose singers tried to keep the pitch lower. Often such a war would go on within the same city as in London. Pitch could vary from somewhere in the 420’s to the mid 450’s. So 440 seems a reasonable compromise!

Phrasing –

February 3, 2010

Nic on performing Brahms: Pt. 3

Flute treatises for the pre-Boehm flute have fingering charts for portamenti. The increasing amount of keywork on later instruments made it harder to glide from note to note, but John Clinton’s Flute Treatise (A Code of Instructions for the Fingering of the Equisonant Flute by the Inventor and Patentee, 1860) shows that the practice did continue into the second half of the 19th century. As he wrote himself: "This ornament is effected by gradually drawing or sliding the fingers off the holes, instead of raising them in the usual manner; by this means is obtained all the shades of sound between the notes, so that the performer may pass from one note to another, as it were, imperceptibly; it produces a pleasing effect, when sparingly used. It is denoted by the mark [shown above the notes above]. The fingers must be drawn off the holes in a line towards the palm of the hand; the employment of the crescendo with the glide heightens the effect."

Flute treatises for the pre-Boehm flute have fingering charts for portamenti. The increasing amount of keywork on later instruments made it harder to glide from note to note, but John Clinton’s Flute Treatise (A Code of Instructions for the Fingering of the Equisonant Flute by the Inventor and Patentee, 1860) shows that the practice did continue into the second half of the 19th century. As he wrote himself: "This ornament is effected by gradually drawing or sliding the fingers off the holes, instead of raising them in the usual manner; by this means is obtained all the shades of sound between the notes, so that the performer may pass from one note to another, as it were, imperceptibly; it produces a pleasing effect, when sparingly used. It is denoted by the mark [shown above the notes above]. The fingers must be drawn off the holes in a line towards the palm of the hand; the employment of the crescendo with the glide heightens the effect."Can't contain our excitement anymore...