Until last week, we didn't know that our friend Frank Wing stopped by in March to snap photos of Jordi working with the orchestra during rehearsal. Check them out.

Until last week, we didn't know that our friend Frank Wing stopped by in March to snap photos of Jordi working with the orchestra during rehearsal. Check them out.Formerly the official blog of Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra – Please visit our website for our new blog

April 28, 2010

Great photos from our March Concert with Jordi Savall!

Until last week, we didn't know that our friend Frank Wing stopped by in March to snap photos of Jordi working with the orchestra during rehearsal. Check them out.

Until last week, we didn't know that our friend Frank Wing stopped by in March to snap photos of Jordi working with the orchestra during rehearsal. Check them out.An influential afterlife: Exploring Orlando Furioso Part 3

April 19, 2010

Seven Centuries of Tradition: Exploring Orlando Furioso Part 2

While our April concerts are over (read the reviews), we are not done with Orlando just yet. Michael Wyatt joins us again:

Orlando furioso is the continuation of an earlier, unfinished, epic poem, Orlando innamorato (Orlando in Love), written in the late fifteenth century by another Ferrarese courtier, Matteo Maria Boiardo, both texts drawn from a wild mix of popular tales and cultivated literature that had developed over almost seven centuries in several linguistic and cultural traditions, encompassing both the Arthurian legends of Britain and the stories which had grown up around the figure of Hrolandus (Roland in French, Orlando in Italian), an obscure eighth-century French warrior.

The principal narrative axes of Ariosto’s poem are two. In the first, Orlando – chief among the Emperor Charlemagne’s Christian knights in the fight against the Saracen Agramante, King of Africa – is rejected by Angelica, daughter of the King of Cathay (China), goes mad, and in the process all but loses France to invading Islamic forces. Orlando’s tortuous return to sanity is only achieved late in the poem, after his English cousin and comrade-in-arms, Astolfo, travels to the moon where the wits of the insane are preserved in jars, watched over there by St. John the Evangelist. The second narrative crux concerns the ever-frustrated love of Ruggiero – Saracen champion and Orlando’s nemesis – for the Christian lady-warrior Bradamante, and the apparently countless impediments blocking their destiny – foretold early in the poem by the magician Merlin – to establish the Este dynasty.

The poem thus links the medieval struggle of Christians and Muslims, refracted through a complex web of history and mythology, with the contemporary reality of early sixteenth-century Italy, itself suffering at the time from a devastating succession of foreign incursions.

Prints by Gustave Dore.

April 8, 2010

Meet Goldilocks

Written in his spare time: Exploring Orlando Furioso Part 1

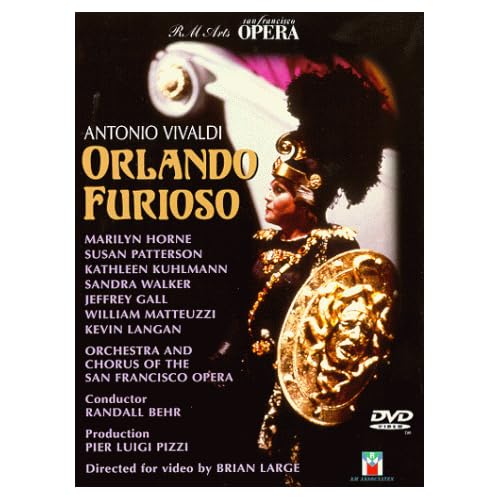

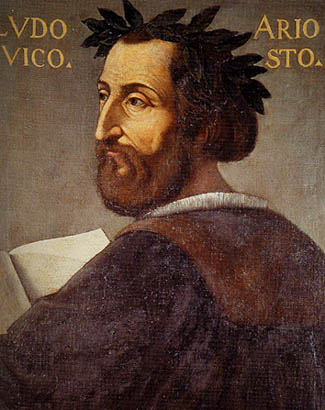

In our last blog post, we mentioned Stanford University's symposium "Mad Orlando's Legacy," which will explore the immense impact of the epic poem Orlando furioso by Ludovico Ariosto, which also happens to be the source material for our April concerts featuring Handel's Orlando. To help us explore the connection between the Renaissance poem and the baroque opera, Michael Wyatt (Associate Director of the Center for Medieval and Early Modern Studies at Stanford University) joins us for a three part blog post. His first is about the author of this epic poem with it's own epic story:

Though now recognized as one of the towering figures of Italian Renaissance culture, Ludovico Ariosto (1474-1533) spent his working life in the service of the Este lords of Ferrara. This city, north of Bologna, is now a sleepy university town but in the early modern period was at the cross-roads of a vast European struggle to gain control of the Italian peninsula, and Ariosto’s great epic poem, Orlando furioso (Mad Orlando), registers these conflicts in multiple ways.

Ariosto was born into a minor aristocratic family and studied both law and classical literature, but the premature death of his father exposed the precariousness of the family’s financial situation and compelled Ludovico into the role of bread-winner for a large clan, first as a diplomat, then as the governor of Este-controlled territories in the isolated mountainous region of the Garfagnana (to the north and east of Lucca), and finally back in Ferrara as master of ceremonies and entertainments for the Este court.

As with so many other major Renaissance writers, Ariosto’s extraordinary literary work was accomplished amidst other – frequently onerous – responsibilities, and Orlando furioso slowly took shape over the course of three decades. First published in 1516, Ariosto continued tinkering with his poem and brought out expanded versions of it in 1521 and 1532. In addition to the Furioso, Ariosto wrote other poetry – in both Italian and Latin – and he was among the first to write stage comedies in a European vernacular language. A series of Satires provide biting send-ups of some of the most prominent figures in Ariosto’s world (including the reigning pope, Leo X, or Giovanni de’ Medici).